Running with mates not long ago, a topic that sparks no end of debate came up: how do you pace yourself for a race, especially an ultra?

(1) Run as evenly as possible.

(1) Run as evenly as possible.

(2) Run hard from the start and try to hang on.

(3) Run easy to start and "negative split" by running further/faster in the second half compared to the first.

Given my recent 6 hour race and thoughts of 12 and 24 hour races dancing in my head, I thought it would be good to actually review what the research says on this, rather than just keep talking "folklore." I've been part of several conversations that sound like this: "Well, you know X runner just did Y (time/distance) at Z race last month. His splits were A/B, so ...."

I thought the research could given me a greater sense of what best practices might be.

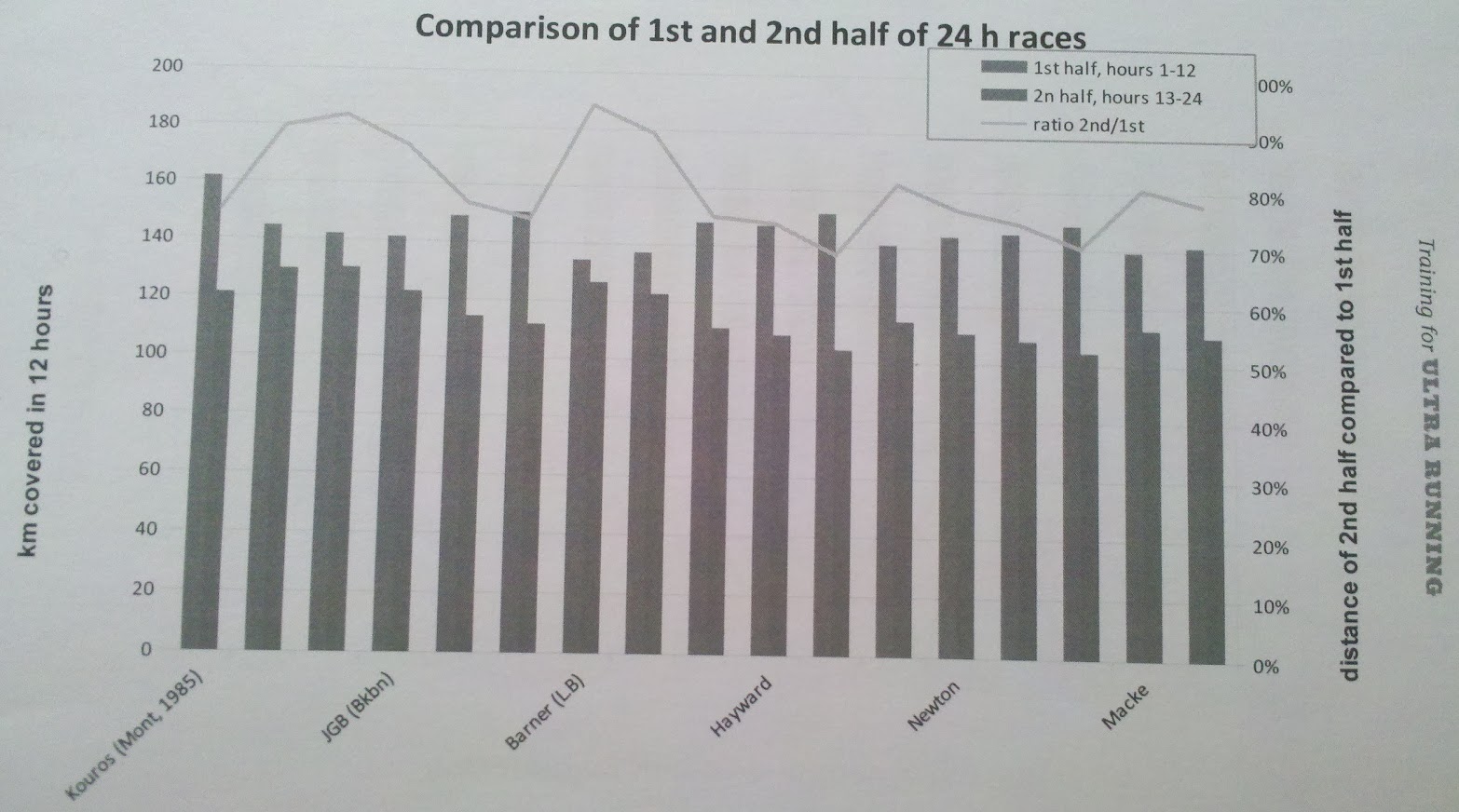

First stop, Andy Milroy's 2013 book, "Training for Ultra Running." There are some wonderful graphs in the back appendix showing what top men, including Kouros and Newton, have done in several of their 24 hour events. Comparisons were succinct, in that they show splits only for "1st half" and "2nd half" and the ratio of performance derived from each. The average ratio for 17 performances was 87.4% for the 2nd half (distance run in 12 hours) compared to the 1st half. Only one of the 17 performances included a negative split (103% in the 2nd half).

Second stop, I went to DUV statistics and pulled up the 12 hour splits and 24 hour distances for 7 of the world's best recent females, including Suzanna Bon and Sabrina Little. None of them had a negative split. Their average ratio was 87.9%. The same as men, essentially (though I took a smaller sample). Interestingly, for those who know of world record holder Mami Kudo, her 2010 and 2011 Soochow performances had ratios of 81% and 74%, so when they are added to the women's results, the female ratio drops to 85.6%.

So far, it seems that elite 24 hour runners do not negative split and they slow by 12-14% in the 2nd half compared to the 1st half.

Out of curiosity, what about my own few 24 hour races? Sri Chinmoy 2010 (first ever) = 76% ratio. World 24 hour 2013 (bad mental mojo) = 77%. At first glance, you either guess I'm going out too hard or there's something else causing me to blow up in the second half. In 2010, I ran exactly what I predicted. For my first serious endurance event, I think 76% was acceptable. In 2013, I expected much more from the 2nd half, but had 3 "sulk" breaks due to the bad mental place I had been in over many months of "over-lifing." I had expected something more like 84%. We have yet to see if I really can perform better, as I think.

Back to the research. Next up, a review of some research studies. In sprints, my quick glance says runners start hard and slow down (e.g., over 800 metres). In longer races, say 5k and 10k, both "moderately trained runners" and world record holders do best by running hard to start, fading a bit, and running hard to finish. Their performance looks like a U shape (with the second 'up' swing in speed not necessarily reaching the height of the first on a graph!). Maybe saying it looks like a backwards tickmark (checkmark) is more apt.

What about events that are even longer? And how hard of a pace is "hard" for starting?

A study published in 2004 analysing the performance of 67 male finishers at the IAU 100k world championship road race in the Netherlands found that the best performing men not only started faster but maintained their starting speed for at least half the race, and finished within 15% of their start speed. Hmmm, 15% drop - that's about what we saw in the 24hr runners. The worst performers at the 100k championships couldn't maintain their pace for very long and dropped pace markedly over the distance. So, although they started out "easier" than the "A" group in terms of pace, perhaps it was still too hard of a pace for their own ability. And/or they lacked the endurance to hold it?

Another study (2013), rather elegant, had cyclists do a self-paced 20k time trial. Get it done as fast as possible. Then they made them do it again later, twice, each time with a different rule. Rule one was that their bikes were set to an average power equated with their original self-paced ride...they just had to ride to 20k again...and keep going if they still could. If they could go further when on the "even pace" rule, then even pacing must be more efficient than doing their self-paced thing. The "Rule two" trial was that they were supposed to stay at their average power but the bike wasn't set to it - thus, more brain power was required to try to stay on that pace. But at the same time, minor variations could then be possible. The result? Nine of the 15 guys QUIT before 20k! The quitters only got 10-15k done. They also reported more negative feelings during the "even pace" rule trials (for both rules) and their rating of perceived exertion was higher. The DNF guys were all guys who had started faster in their original self-paced ride. They rode the 1st third of the distance at 1-2% above their mean power output for the 20k. The 6 guys who managed to finish the 20k during the "even pace" rule had started conservatively in their original self-paced time trial (riding the 1st third of the distance at 1-4% below their mean power). AND, notably, those 6 guys were able to cycle 20-27k during the "even pace" rule. This again provides evidence that trying to run conservatively or "even" at the start means one will be left with too much petrol in the tank at the end...under-performance.

I thought I'd look at my recent 6 Hour performance, which I felt was a solid run for me. I ran 74.930km in 6 hours. That's a 4.48min/k average. The 1st third of the event I ran 25.6km. That's a 4.41 pace. And that just happens to be 2% faster than my average.

The research suggests that had I run up to 5% faster in the 1st third, that is a 4.34 pace, I likely would have blown up. My "central governor", the brain process coined by Tim Noakes, would have choked me along the way. It's the theorised governor that keeps a watch on body systems with a view to keeping us from killing ourselves. It's monitoring our body heat, sweat rate, muscle work rate, carb stores, levels of oxygen in the blood, and so on. It sends us "tired" signals to slow us down, recruit less muscle and cause less strain to the heart. Although we are "self-paced," our pace is still decided by this purported governor, which analyses what's "safe." And that's why, if we are suddenly told the finish line is further than we thought, we feel more tired! The governor makes a new calculation, given the change in one variable, and says, "Well, given the rest of the conditions remaining the same, we must slow down to survive." But, if we then get some more glucose, the weather cools and we are sweating less, or someone tells us there was an error and we are actually CLOSER to the finish line, we SURGE! The governor adjusts the "fatigue" signals, knowing it's now safe to up the pace. And that gives us the parabolic/reverse tickmark profile for so many of our ultra distance events.

In sum, my take-away messages from the research, my experience, and the "folklore" chats with mates are:

1. Run well within yourself.

2. Given point #1, the starting pace should feel comfortable and easy, but will still be faster than your overall average pace for the race. How much faster? In races up to 6 hours, appropriate pace may equate to about 2% faster than the anticipated mean pace for the entire race. In races of 24 hours, based on a quick analysis of those top women's 24hr performance at World 2013 Championships, the first 6 hours was done at an average of more than 30 seconds faster per minute/km. In other words, they were about 10% faster (range 6-13%) in the first six hours compared to their average for the entire race. Extrapolating to the 12 hour event, one might start at a pace that was 5% faster than the anticipated average race pace.

3. At the half-way point, it shouldn't feel "hard" yet (this little rule of mine seems to fit for races from 5k to 24hr so far).

4. Run your own race. This has been hammered home again and again to me. I found out at the Coburg 6 Hour last month, I was tied for 5th place overall at the halfway point. By finish time, I had passed three of those men, to move to 3rd overall. I ran my own race and didn't get caught up in who was on what pace/distance/position. I've also been on a track enough times to see many of the walkers in the concurrent race-walking events out-perform runners!

5. Endurance improves over time/experience. My ability to sit on a pace for a certain length of time has continued to improve as I've gotten fitter and the body has adapted.

6. Keep the perceived exertion down. Take caffeine, take beetroot juice, tell yourself lies about how easy it feels, and have everyone else tell you how great and effortless you look :)

(1) Run as evenly as possible.

(1) Run as evenly as possible.(2) Run hard from the start and try to hang on.

(3) Run easy to start and "negative split" by running further/faster in the second half compared to the first.

Given my recent 6 hour race and thoughts of 12 and 24 hour races dancing in my head, I thought it would be good to actually review what the research says on this, rather than just keep talking "folklore." I've been part of several conversations that sound like this: "Well, you know X runner just did Y (time/distance) at Z race last month. His splits were A/B, so ...."

I thought the research could given me a greater sense of what best practices might be.

First stop, Andy Milroy's 2013 book, "Training for Ultra Running." There are some wonderful graphs in the back appendix showing what top men, including Kouros and Newton, have done in several of their 24 hour events. Comparisons were succinct, in that they show splits only for "1st half" and "2nd half" and the ratio of performance derived from each. The average ratio for 17 performances was 87.4% for the 2nd half (distance run in 12 hours) compared to the 1st half. Only one of the 17 performances included a negative split (103% in the 2nd half).

|

| First half compared to second half. Start too hard, just finish weaker. See that trend? |

Second stop, I went to DUV statistics and pulled up the 12 hour splits and 24 hour distances for 7 of the world's best recent females, including Suzanna Bon and Sabrina Little. None of them had a negative split. Their average ratio was 87.9%. The same as men, essentially (though I took a smaller sample). Interestingly, for those who know of world record holder Mami Kudo, her 2010 and 2011 Soochow performances had ratios of 81% and 74%, so when they are added to the women's results, the female ratio drops to 85.6%.

So far, it seems that elite 24 hour runners do not negative split and they slow by 12-14% in the 2nd half compared to the 1st half.

Out of curiosity, what about my own few 24 hour races? Sri Chinmoy 2010 (first ever) = 76% ratio. World 24 hour 2013 (bad mental mojo) = 77%. At first glance, you either guess I'm going out too hard or there's something else causing me to blow up in the second half. In 2010, I ran exactly what I predicted. For my first serious endurance event, I think 76% was acceptable. In 2013, I expected much more from the 2nd half, but had 3 "sulk" breaks due to the bad mental place I had been in over many months of "over-lifing." I had expected something more like 84%. We have yet to see if I really can perform better, as I think.

|

| 1995 IAU 100k. Group A was fastest, G slowest |

What about events that are even longer? And how hard of a pace is "hard" for starting?

A study published in 2004 analysing the performance of 67 male finishers at the IAU 100k world championship road race in the Netherlands found that the best performing men not only started faster but maintained their starting speed for at least half the race, and finished within 15% of their start speed. Hmmm, 15% drop - that's about what we saw in the 24hr runners. The worst performers at the 100k championships couldn't maintain their pace for very long and dropped pace markedly over the distance. So, although they started out "easier" than the "A" group in terms of pace, perhaps it was still too hard of a pace for their own ability. And/or they lacked the endurance to hold it?

Another study (2013), rather elegant, had cyclists do a self-paced 20k time trial. Get it done as fast as possible. Then they made them do it again later, twice, each time with a different rule. Rule one was that their bikes were set to an average power equated with their original self-paced ride...they just had to ride to 20k again...and keep going if they still could. If they could go further when on the "even pace" rule, then even pacing must be more efficient than doing their self-paced thing. The "Rule two" trial was that they were supposed to stay at their average power but the bike wasn't set to it - thus, more brain power was required to try to stay on that pace. But at the same time, minor variations could then be possible. The result? Nine of the 15 guys QUIT before 20k! The quitters only got 10-15k done. They also reported more negative feelings during the "even pace" rule trials (for both rules) and their rating of perceived exertion was higher. The DNF guys were all guys who had started faster in their original self-paced ride. They rode the 1st third of the distance at 1-2% above their mean power output for the 20k. The 6 guys who managed to finish the 20k during the "even pace" rule had started conservatively in their original self-paced time trial (riding the 1st third of the distance at 1-4% below their mean power). AND, notably, those 6 guys were able to cycle 20-27k during the "even pace" rule. This again provides evidence that trying to run conservatively or "even" at the start means one will be left with too much petrol in the tank at the end...under-performance.

I thought I'd look at my recent 6 Hour performance, which I felt was a solid run for me. I ran 74.930km in 6 hours. That's a 4.48min/k average. The 1st third of the event I ran 25.6km. That's a 4.41 pace. And that just happens to be 2% faster than my average.

|

| My Coburg reverse tickmark |

The research suggests that had I run up to 5% faster in the 1st third, that is a 4.34 pace, I likely would have blown up. My "central governor", the brain process coined by Tim Noakes, would have choked me along the way. It's the theorised governor that keeps a watch on body systems with a view to keeping us from killing ourselves. It's monitoring our body heat, sweat rate, muscle work rate, carb stores, levels of oxygen in the blood, and so on. It sends us "tired" signals to slow us down, recruit less muscle and cause less strain to the heart. Although we are "self-paced," our pace is still decided by this purported governor, which analyses what's "safe." And that's why, if we are suddenly told the finish line is further than we thought, we feel more tired! The governor makes a new calculation, given the change in one variable, and says, "Well, given the rest of the conditions remaining the same, we must slow down to survive." But, if we then get some more glucose, the weather cools and we are sweating less, or someone tells us there was an error and we are actually CLOSER to the finish line, we SURGE! The governor adjusts the "fatigue" signals, knowing it's now safe to up the pace. And that gives us the parabolic/reverse tickmark profile for so many of our ultra distance events.

In sum, my take-away messages from the research, my experience, and the "folklore" chats with mates are:

1. Run well within yourself.

2. Given point #1, the starting pace should feel comfortable and easy, but will still be faster than your overall average pace for the race. How much faster? In races up to 6 hours, appropriate pace may equate to about 2% faster than the anticipated mean pace for the entire race. In races of 24 hours, based on a quick analysis of those top women's 24hr performance at World 2013 Championships, the first 6 hours was done at an average of more than 30 seconds faster per minute/km. In other words, they were about 10% faster (range 6-13%) in the first six hours compared to their average for the entire race. Extrapolating to the 12 hour event, one might start at a pace that was 5% faster than the anticipated average race pace.

3. At the half-way point, it shouldn't feel "hard" yet (this little rule of mine seems to fit for races from 5k to 24hr so far).

|

| The Coburg scoreboard at 3 hours, which I saw as a photo post-event |

5. Endurance improves over time/experience. My ability to sit on a pace for a certain length of time has continued to improve as I've gotten fitter and the body has adapted.

6. Keep the perceived exertion down. Take caffeine, take beetroot juice, tell yourself lies about how easy it feels, and have everyone else tell you how great and effortless you look :)

You might be interested in this:

ReplyDeletehttp://ultrastu.blogspot.co.nz/p/article-pacing-strategy.html

Basically, “Run as fast as you can, WHILE you can!”

I'm not sure that's a strategy for beginning ultra runners (like me!) but it's an interesting viewpoint I think.

Thanks, Mike. I ran with Stuart at World Trails - interesting first bit to that post. The fact that the fastest 100 Mile times have been done with totally different strategies certainly suggests somewhat the "horses for courses" idea, where our approach has to fit us individually as a runner. And no matter the actual amount of split (certainly no negative split), I would hazard a guess they each ran a pace to start that felt "comfortable and easy" for them and "well within themselves."

Delete"Run as fast as you can, while you can" is a bit dramatic/over-the-top, I think. I actually don't even think Stuart quite means that, as he does say he's running "below my maximal lactate steady state (MLSS)" and he's able to keep fuelling. So that's not really "as fast as he can." He's still running "comfortably."

I do agree with the idea that running REALLY slowly at the beginning with some goal of negative splitting is not a good one. Another key aspect I really wonder about is the perceived exertion side of things. When these guys run harder earlier and then are slower later (see Hayward's three races in the first graph above), do they feel more like crap in the second half? In the end, Hayward probably ran similar distances in all three of those events in that graph - but he seemed to have three different pacing strategies for the first half. And the harder he started, the harder he fell.

Very good BBC. Fantastic post. Will try to remember, take on board some of these ideas which make a lot of sense, and further evidence that negative split = under performance as I have suspected for more than a decade.

ReplyDeleteMy best races over all distances have that inverted tick pattern, start fast, hold pace and then finish strong, but a touch slower than my start... I think the timing of the hills at 6 inch and 6 foot affects the pacing a bit for me anyway with my inferior ascending, since at 6 inch there is goldmine hill in the first 2k, and at 6 foot there is the 400m drop of the steps in the first few k, and th 800m climb from 15k to 26k... I think I might try applying that 2% rule to my goal pacing in half marathon and marathons if I can remember in my messy life.

What about high levels of testosterone in Men (one advantage or disadvantage sometimes? that Men have compared to Women in racing), combined with adrenaline and mental psyching up for races?

When I was younger myself and many others in the track & field scene often would listen to 1. very aggressive music, or 2. music that may not have been aggressive but had strong inspirational/meaningful effects for us, as strategies to ensure we really started very strongly early, and held a strong pace in the first 30% of the race.

I particularly remember being very focused and intensely psyched up early on when I racewalked a 1500m in 6min 15 and also in the Australian Masters 1500m on track in 2010 early on, 2011 Melbourne Marathon (starting with a 2.11 Kenyan marathoner), 2013 Perth Marathon with Roberto doing his 2.24 marathon, etc etc...

I remember sharing a room with a sprint hurdler (110m hurdles, or similiar distance) at Junior National championships when I was racewalking for WA around 1989-1993, and on raceday he really psyched up before and at the start and really got "in the zone" "tunnel vision" to have the quickest possible reaction time to the gun at the start and then attacked the first few hurdles with very intense focus (and good technique). Nice to read about some data out there on the pacing patterns of the best runners, and what degree of positive split they are doing.

Trailblazer, there is some evidence to support the theory that testosterone can be an ultra runner's downfall! Why do women do so well in long ultras - often outperforming men? Why do "old" men often outperform younger men? Both groups (women and older men) have less testosterone. The testosterone seems to induce a little too much of a competitive push...the "go out too hard" thing. So, there are two good reasons to be an aging female ;)

DeleteMarathon has some good stats, because it's 'short' enough that there are a lot of attempts by runners with very well documented capabilities (that lie almost exactly on distance vs time prediction curves), but still long enough that many, many elite runners absolutely botch them.

ReplyDeleteIf you take an elite runner's 'potential'* pace for a marathon, and they run 5 to 10 seconds per km too fast at the start, you can accurately predict the point it will all go pear shaped, and when it does it goes bad in a big way.

But the best ever results for marathon line up with what you have said - they start and finish slightly faster, and slow a bit in the middle. But it isn't much - I had the km splits for Haile Gebreslassie's world record at one point, and I think he started and finished at 2:54/km, and 'slowed' in the middle to 2:57/km. Kipsang's marathon world record 10km splits were 29:17, 29:02, 29:42 and 29:11.

But for 6 hour + events, I think there is still a bit of mystery out there. I would love to know your splits for the Coburg 24 hour you just did.

I would guess the 3 energy systems ATP-PC (Adenosine Tri Phosphate-Phosphate Creatine), Anaerobic and Aerobic and the switch from mostly Carbohydrates to mostly Fats would be factors in differences in best pacing strategies for a variety of distances. At least thats what I tried to learn about at Uni in the mid 1990's...

ReplyDeleteI think BB's halfway splits at Coburg 24 hour in her massive National Records were something like 125k first 12 hours and 113km 2nd 12 hours, so certainly a positive split there in a performance that is likely to be top 5-10 in the world this year?

I think you can have success using a variety of pacing strategies if you use the strategy wisely and correctly. The most optimum strategy of all strategies I think is debatable, but I'm convinced a positive split is a common and good strategy, although that maybe a very small slowdown...

Sounds like in the Kipsang WR splits he started fast in the first 20km, (fastest 5k in 14.29 15k-20k) slowed up a lot in the 3rd 10km (slowest 5k of 14.54), and then gathered himself, adjusted to change in energy system ratios of Carbs and Fats? to bring it home in the 4th 10km split at a similiar pace to his first 20km, but not quite as fast as his 2nd 10km. Of course there is another 2.2km as well at the end, but its clear he spent most of the race at a pretty even pace around the 2.55 per K mark.... http://spikes-mag.tumblr.com/post/62707576962/wilson-kipsangs-world-record-in-numbers

I had a look at Martin Dents 1km splits in the World Champs Marathon in Moscow last year (its on strava.com), and his first few K's were very fast (although some reckon his Garmin may have made errors, because it was a few laps on a circular track in the first Km... But I think its obvious he started strongly...

The Science of Sport people often have a few interesting things to say. Here is a link to their analysis of the London Marathon the other week. Kipsang won in 2.04.29, Edna Kiplagat the Womens and debuts from Mo (2.08!) and Dibaba (3rd woman!!!!)

http://www.sportsscientists.com/2014/04/london-marathon-live-splits-and-analysis/